CHILDREN EIGHTY YEARS YOUNGER THAN HE IS can sing his songs. Folk musicians around the world play an instrument that bears his name. An American rock icon releases a tribute album to coincide with his eighty-seventh birthday. The Kennedy Center honors him for lifetime achievement in the same city that nearly jailed him for subversion decades earlier. A fundamentally simple man, he wears his accolades with a frank and modest demeanor that puts literally to shame the self-aggrandizing, chest-thumping atonal frauds and mass production empty vessels who are called musicians today. He is both the first and last of a breed of whose creation he was a major part. He is an American original. He is Pete Seeger.

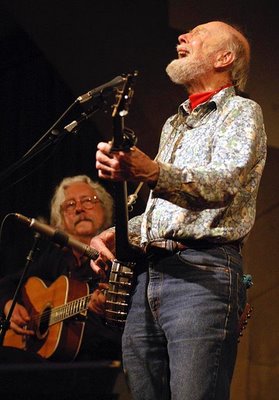

CHILDREN EIGHTY YEARS YOUNGER THAN HE IS can sing his songs. Folk musicians around the world play an instrument that bears his name. An American rock icon releases a tribute album to coincide with his eighty-seventh birthday. The Kennedy Center honors him for lifetime achievement in the same city that nearly jailed him for subversion decades earlier. A fundamentally simple man, he wears his accolades with a frank and modest demeanor that puts literally to shame the self-aggrandizing, chest-thumping atonal frauds and mass production empty vessels who are called musicians today. He is both the first and last of a breed of whose creation he was a major part. He is an American original. He is Pete Seeger.There is a hint of the timeless about the man. He never looked young, even when he was, and now that he is well into his ninth decade, he wears his age with the same grace that he held and played that now-famous long-necked banjo. Seeger has godfathered three younger generations of musicians, and nothing lends credibility to a folksinger as much as an association with ol' Pete does. He has spent nearly seventy years singing songs, through decades of wars and depression and peace and prosperity, always with an unarticulated faith that if he could just get folks singing together then somehow things would work out for the best. From his wanderings with Woody Guthrie to union rallies and migrant camps and with the Almanac Singers and the Weavers through their rise and fall - from pressing Bob Dylan and Joan Baez into freedom rides and demonstrations in the Deep South in the Civil Rights era through his cruises up and down the Hudson with Arlo Guthrie to cleanse that desecrated waterway - Pete Seeger has just kept on singing, and he wanted all of us to sing along with him.

A half dozen at least of his songs will likely outlive him by a century or more. While everyone knows that Pete wrote Where Have All The Flowers Gone? and Turn! Turn! Turn! and co-wrote If I Had A Hammer with fellow Weaver Lee Hays, few are aware that folk classics Guantamera and Wimoweh (The Lion Sleeps Tonight) would have lain fallow in their countries of origin had not Seeger discovered, re-arranged, and introduced them to American audiences. Fewer still are aware that the present form of We Shall Overcome, originally a religious and labor song before it became a civil rights hymn and just about every activist's favorite anthem, owes its arrangement and many of its lyrics to the lanky Harvard drop-out with that impossibly long banjo.

That Seeger's supposed politics remain problematic for some is simply an indication of the extent to which Pete subsumed himself into his music. Not given to rants, Pete always tried to let the songs speak for him. That he was a socialist or communist or radical leftist is beyond question. But HUAC and McCarthy and the FBI never quite understood what Pete was up to. Seeger's activism had more in common with the utopian communards of nineteenth century New Harmony or Brook Farm than it ever did with sleeper cells or comic-opera type Commies who drummed out the vote for Gus Hall for forty years. If you want to understand Pete's collectivism, you have to look not in Trotsky or Lenin but in Carl Sandburg's The People, Yes! or Whitman's Leaves of Grass. Like those classic American poets, Pete Seeger had an unshakable belief in the uncommonness of the Common Man, in the ultimate destiny that the rights of the many would prevail over the privileges of the few. You can see the Seeger brand of social collectivism more accurately in an Amish barn-raising than you can in a screed from any of today's misnamed "leftists."

All you have to do is just listen to him sing. His voice is sweet without being especially refined or trained; it has a throatiness and flatness of accent that brands it as unmistakably and universally American. It reminds you of the delightful and classic short story The Devil and Daniel Webster in which Stephen Vincent Benet relates the tale of an unfortunate New Hampshire farmer who in a moment of weakness has sold his soul to the Devil himself. In an effort to stay out of Hell, the farmer implores the legendary Daniel Webster to plead his case for him. Things seem to be going badly until Webster reaches his summation. Benet tells us

...he wasn't pleading for any one person any more, though his voice rang like an organ. He was telling the story and the failures and the endless journey of mankind. They got tricked and trapped and bamboozled, but it was a great journey....The fire began to die on the hearth and the wind before morning to blow.... And his words came back at the end .... For his voice could search the heart, and that was his gift and his strength. And to one, his voice was like the forest and its secrecy, and to another like the sea and the storms of the sea; and one heard the cry of his lost nation in it, and another saw a little harmless scene he hadn't remembered for years. But each saw something.